- What problem does docker solve?

- What is containerization?

- Running Docker on your machine

- What are the building blocks of Docker?

- Docker images

- Running your first container

- Working with containers

- Executing commands in a running container

- Data in Docker containers

- How to build your own Docker image?

- Docker compose

- Wrap up

**Update****** Now you can follow along the video and learn with my youtube tutorial.

So you decided to learn Docker? This tutorial, unlike other tutorials, takes a solution focused approach, rather than a toolkit focused approach. We start from the big picture, understanding what problems Docker is meant to solve and start using Docker as we make progress.

I will use an experience from a recent project and solve common computing challenges I had to face. I think I could have solved such challenges with much less headache if I had this tutorial. So I decided to write it.

I rolled out the new version of my affiliate site recently. I used a lot of cool tech in this project, I built an isomorphic React app with Redux, I also wrote a Wordpress theme that turns Wordpress into a backend with a proprietary REST API.

During this project I faced the challenge of deploying several components to different environments. That’s how I met Docker.

I found a lot of tutorials on-line, but struggled to understand if the information is still relevant and if I still need all the tools used in those tutorials. Even Docker itself focuses more on how to use certain tools and does not provide the big picture on the website.

So in this tutorial we’ll start from the big picture, with a state-of-the-art overview of what you need and what problems will those tools solve for you in the first place.

In the beginning let me give you my short and concise definition of the problem Docker is built to solve. So we’ll start from there and move on step by step.

What problem does docker solve?

This is the fundamental question of everyone who wants to start out with Docker. Let’s answer the question in the clearest and simplest way possible, with everyday words, not Docker terminology.

What problem does Docker solve? Docker solves the problem of having identical environments across various stages of development and having isolated environments for your individual applications.

The problem itself is as old as software development. Environment setup and management is a tedious task in every project.

In the old days we used custom scripts for that. We used to host various different applications on the same physical machine without any virtualization. It was usually a configuration nightmare to juggle with environment variables, trying to keep applications independently configurable or using two different versions of the same technology (like Java) on the same machine.

It used to be common practice to run your production applications on dedicated machines, while development or test environments were clattered with a lot of different applications to save hardware cost. In these cases your development and test servers were configured much differently than your production server.

Our infrastructure teams used to create different environment scripts for different stages, like development, test, staging and production. These environments were not identical, just mostly similar.

On top of all this, we used to do our local development and unit testing on Windows machines, while all other stages were run on Unix systems.

Working like this was not impossible, but it was a costly, time consuming effort to manage these environments with a lot of inherent risk that caused a lot of quality issues in all stages.

Docker provides a solution to this problem with containerization.

What is containerization?

Containerization means, that your application runs in an isolated container, that is an explicitly defined, reproducable and portable environment. The analogy is taken from freight transport where you ship your goods in containers.

A container of an app is the app’s operating environment in our computing scenario. With Docker you ship the operating environment along with your application.

Containerization is not a new phenomenon, Linux Containers have been around for a while already, added to the Linux kernel in 2008. You can google LXC to learn more about the topic.

Linux containers aim to solve the same problem. They are self contained execution environments that act like they were standalone Linux machines, they have their own dedicated hardware resources. In reality they are not separate machines, because containers run on top of the same Linux kernel.

In other words you can install one Linux system and create several containers on top of it, that you can use as isolated machines, while they are actually running on the same Linux machine and share most of the core resources.

The key here is resource sharing. Docker started out creating specialized Linux containers. The idea is the same. You don’t need a separate, full blown physical or virtual machine to give isolated environments to your applications.

You can put your applications into containers that share most resources amongst each other. Containers are only different in the necessary minimum that is required to behave like an isolated environment.

The strength of Docker is that they have gone through the tedious task of stripping of all common stuff from containers and leave the bare minimum inside for separation. This way they created a flexibility and portability we’ve not seen before in environment management.

Let me give you an example of the containers I have on my local machine so that you get a better idea. Docker and the community say that every container should have one main executable. In practice I translated this to one application per container. These are the running containers on my Mac right now:

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED

STATUS PORTS NAMES

f3c88680252a jwilder/nginx-proxy "/app/docker-entrypoi" 3 weeks ago

Up 32 seconds 0.0.0.0:80->80/tcp, 0.0.0.0:443->443/tcp nginx-proxy

ff25d1fb2770 mariadb "docker-entrypoint.sh" 3 weeks ago

Up 32 seconds 0.0.0.0:3306->3306/tcp mariadb

As you can see I have two containers running locally. One of them is an nginx proxy and the other one is mariadb.

If you look at the ports, you can see that nginx proxy is listening on port 80 and 443, which means that this is my active http://localhost server.

Similarly, mariadb is listening on the default port, which means that this is my local mysql instance. Yeah, I connect to it with a mysql client (SequelPro btw.) and do my database stuff. It’s just like any other running mysql server.

Well, I’m not running apache or mysql on my Mac anymore. I do my development in Docker containers.

I’ll tell you a lot more about this, I just wanted to show a few containers running. Now if I wanted to work on a Wordpress site, for example, I could start a Wordpress container next to nginx-proxy and mariadb and make these guys work together.

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED

STATUS PORTS NAMES

f3c88680252a jwilder/nginx-proxy "/app/docker-entrypoi" 3 weeks ago

Up 11 minutes 0.0.0.0:80->80/tcp, 0.0.0.0:443->443/tcp nginx-proxy

1c8ebe30f62a wordpress "/entrypoint.sh apach" 3 weeks ago

Up 3 seconds 80/tcp vs-api

ff25d1fb2770 mariadb "docker-entrypoint.sh" 3 weeks ago

Up 11 minutes 0.0.0.0:3306->3306/tcp mariadb

As you can see now, I have three containers running, I started Wordpress next to the other applications.

My applications are running in separate containers in isolated environments. I can now replicate or re-create the same environments on another laptop or on my production VM using a few Docker commands, one command per application to be precise. (OK, and some magic for git).

No local apache configuration, no document root settings, no playing around with ~/Sites (sounds familiar? :), no mysql installer, no brew, just portable containers. Life is so much easier.

So let’s make it happen for you, too. Let’s install docker first, and then talk about the terminology around containers a bit. Once we have this, I bring you up and running.

Running Docker on your machine

In order to use Docker on your local machine or on your server, you need Docker Engine. You can download and install Docker Engine for Mac, Windows and Linux from the Docker site, follow this link.

Please note that the way we run Docker on Mac and Windows used to be much different not too long ago. I’m writing this on October 13th, 2016. If you see tutorials that say that you need Docker Toolbox, Docker Machine or boot2docker to run docker containers on Mac and Windows, then be aware that those are outdated.

Those tools were required because Docker did not have native support on Mac and Windows, so you had to run a virtual machine and Docker Machine and boot2docker gave you the tools to do that.

Today Docker for Mac and Windows give you native tools to run docker on your machine. They run Linux under the hood, but it’s incorporated into an official native app. You may still find yourself in situations when you need Docker Toolbox or boot2docker, one such scenario is when you use a Mac produced before 2010.

Installation of Docker for Mac and Windows is done with a wizard, please follow the steps and come back when you are done. Linux installation requires a few more manual steps, you’ll find distro specific instructions on the Docker link above.

When the installation is complete you should have Docker Engine up and running on your machine.

If you are on Mac, you can check the little whale icon in the top bar near the clock. You should be having the necessary command line tools to run containers. Let’s check if this is the case. Let’s run these commands in the Terminal app.

➜ ~ docker --version

Docker version 1.12.1, build 6f9534c

➜ ~ docker-compose --version

docker-compose version 1.8.0, build f3628c7

docker --version and docker-compose --version show the version information of two essential Docker tools. If the above works, you are ready to move on to the next step.

What are the building blocks of Docker?

We have seen the containers I’m running on my machine. Let’s see where they come from.

The three containers I had up were nginx proxy, mariadb and Wordpress. I created them from Docker Images. Let’s look at this terminology.

A Docker image is the definition of a container. To make it really clear, an image is like a snapshot a software component. It contains the required executables, environment settings, so that it gives you a turn key solution. You just type docker run and a preconfigured image will be used to start a container.

In other words a container is a running instance of an image.

You can use the same image to start multiple containers. You can add runtime parameters to adjust some settings like port mappings, shared volumes and such.

The first thing you need for your development is the image that servers your goals.

Docker images

Images may come from two sources:

- image repository, I use the Docker Hub, I’m not aware of any other significant repository, the hub serves me well.

- you can create your own images. We will talk about this in more details, because this part is awesome. Docker images are layered, so you can build them layer by layer, and you can build your images starting from other images.

Let’s just visit Docker Hub and lay your hands on your first image. You can sign up if you want to, you don’t need a registration to browse and use images though.

On the page you’ll see a list of images. Most of them have the label “official” , which means that they are provided as the official package of a specific technology. (OK, this is pretty obvious).

Some images are provided by third parties, including community members. Those are usually a bit more specific, they are probably built on top of official packages. You should be seeing popular apps and solutions on that list like node, httpd, wordpress, nginx, Ubuntu and so on. The number of stars and downloads will give you an idea how popular an image is in the community.

Let me show you my machine, before we get your package. I use the docker images command to list images on my local machine.

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID

CREATED SIZE

node 6.6.0 f4e366168fa6

3 weeks ago 650.8 MB

jwilder/nginx-proxy latest 1d942ca55e4f

4 weeks ago 248.4 MB

wordpress latest de013c4e03e8

4 weeks ago 421.6 MB

node latest 348237a1e6c9

4 weeks ago 652.9 MB

mariadb latest 7e149af02fc0

6 weeks ago 391.9 MB

If you remember, I’m running an nginx-proxy, a mariadb and a wordpress container on my local machine. These containers are running instances of the images jwilder/nginx-proxy, wordpress and mariadb in the above list. I pulled those images from the Ducker hub.

I also pulled two node images that I use for my React site. The difference between the two node images above is the version number. One of them is the latest (whatever number that actually is), the other one specifies an exact version number (6.6.0). This is going to be very important later.

One of the key guiding principles of Docker based development is to use explicit version numbers to ensure that your environments are as identical as possible. Which means that my above setup is not ideal, because I use several “latest” versions locally. I’ll fix that soon.

Let’s check out the details of an image on Docker Hub. Let’s click the nginx image (it’s the first item right now on the list, if you don’t see it just use the search bar on the top). Click on the nginx item and let’s look at the page that comes up.

If you never heard of Nginx, let’s just say that it’s a web server. It’s in fact more than that, but we’ll use it as a web server now.

The page says this is the “Official build of Nginx”. This sounds pretty reassuring.

The full description of images usually start with the version listing. This is the part that you’ll be using a lot.

Here you can pick the exact(!) version number you want to use. Every version provides more details behind the links that end in /Dockerfile. Those links will take you to github where you can see how that image is exactly built. A Dockerfile is the file that defines the building steps of images. You can write your own, but let’s talk about this later.

Note that the image has Jessie and Alpine variations (at least right now). This means that we have images built with Debian Jessie and we have images built with Alpine linux. These are both different Linux distributions.

Which one to use, you may ask now. This part of the ecosystem is in change, so you’d better check on-line when you read this post.

These days the situation is, that many official Docker images move to Alpine, because it’s much smaller in size and it’s security focused. Right now Alpine is the direction that Docker images are taking. For the tutorial we can use any of the two.

Moving on, the page explains what Nginx is.

If we want to use this image, we can do two things:

- pull the image with

docker pull. Docker pull will just download the image locally and you’ll see it in your image list. - you can run the image with

docker run, this will pull the image, if it’s not available locally and then run it. Run is just a one step solution to pull and run.

Whichever you use is a matter of personal preference.

Beginner tutorials will tell you to run the image straight away. I build solutions where several containers play together, so I usually pull the big picture first and then start tuning the execution parameters.

So, let’s just pull first. :) We will specify the version when we do so. Let’s pick the alpine variant. Issue this command in Terminal:

docker pull nginx:1.10.1-alpine

If you are wondering about the size difference between Jessie and Alpine, I pulled them both to show the numbers to you:

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID

CREATED SIZE

nginx 1.10.1 bf2b4c2d7bf5

3 weeks ago 180.7 MB

nginx 1.10.1-alpine e84e20a9b8b5

3 weeks ago 54.03 MB

You see that the Alpine image has a smaller footprint, 180.7MB vs 54.03MB.

Let’s continue the tutorial with the Alpine image.

Running your first container

I typed almost a whopping 2900 words so far. All of the above shall become a 5 second routine pretty quickly, so don’t worry, just practice. Take a deep breath, we’ll start our first container.

Please make sure that you’re not running a web server on your local machine on port 80, otherwise we’ll have a conflict. The Terminal command is:

docker run --name my-nginx -p 80:80 nginx:1.10.1-alpine

docker run is the command that starts up containers from images. If it cannot find the image locally it will pull it for you.

With --name my-nginx you can give your container a human readable name. When I run several wordpress containers, I usually use the site name to distinguish my apps. --name is optional, Docker will give your containers funny names if you don’t provide this parameter.

Without -p 80:80 you can’t make the nginx server functional. This parameter maps the container’s port 80 to the host computer’s port 80.

Oh fuck, what does this mean? This is needed because images, and thus running containers, expose pre-defined ports to the external world. Our Nginx container exposes ports 80 and 443 for http and https requests. (I found this information in the Dockerfile of the nginx image on the Docker hub). This means that you can send request to port 80 and 443 of your container. It does not mean that your local machine is listening on these ports.

In order to make a certain application available on your local machine, we have to map its port to the local machine’s port. This is done with -p host-port:container-port, in our case -p 80:80.

The computer that’s running the Docker Engine is called the host computer. In my case the host computer is my Mac, I run the Docker Engine with Docker for Mac. You installed yours at the beginning of the tutorial. So the machine that runs Docker engine is the host machine.

Your ultimate goal is to compose the services of your host with one or more Docker containers. Containers behave like standalone virtual machines. They have their own Linux file system, users, hardware resources, environment variables, executables and so on. Containers expose their services on pre-defined ports.

You may want to run more than one Nginx container on your host machine, when building multiple sites. In my case I run several wordpress containers and node containers on my Mac (and also in production). All your Nginx containers will expose port 80. You gotta find a way to send request to your container’s port 80 from your host machine. Therefore you have to map one of your host ports to the container port.

So what we did above was that we mapped -p host:container, i.e. -p 80:80, which means that http://localhost:80 will be served by your container’s port 80. Since port 80 is the default http port, you don’t need to type that. (oh sorry, I’m going really basic here, but I think there are millions of young kids willing to code, and I wanna give them a chance to keep up). So http://localhost will go to your container’s port 80.

If you wanted to assign a different port on your host, let’s say 8080, you would use -p 8080:80 in the above parameter. This would publish your nginx server on http://localhost:8080.

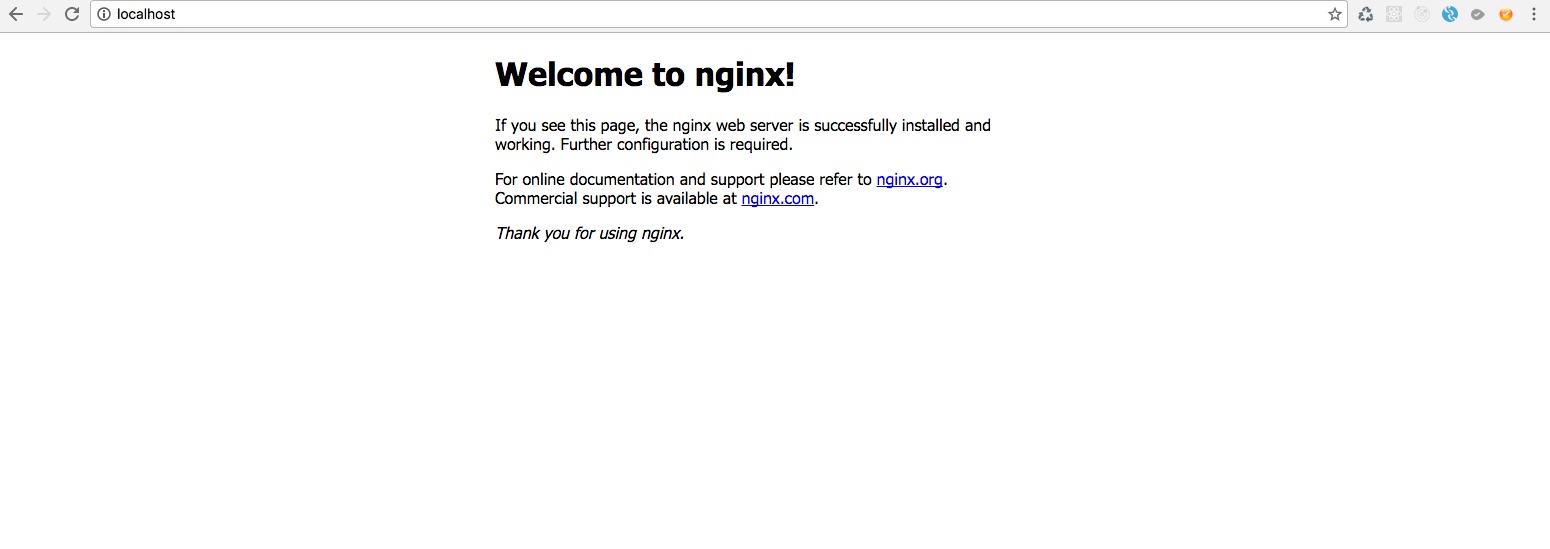

Let’s go back to our original scenario, open your browser now and check http://localhost. You should see this:

Let’s celebrate, you have started a web server with Docker! I know, a few things are missing, but we’ll get to that.

Working with containers

This container is running in the foreground. If you look at your terminal, you’ll see the requests appearing as you refresh the page. Let’s leave it like this for a while and focus on more substantial matters. Let’s open another terminal window, or terminal tab and use the command:

docker ps

You should see something like this:

➜ ~ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND

CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

01041c82947c nginx:1.10.1-alpine "nginx -g 'daemon off"

41 minutes ago Up 41 minutes 0.0.0.0:80->80/tcp, 443/tcp my-nginx

3 weeks ago 54.03 MB

docker ps gives you the list of running containers. These containers are pre-configured running applications. This gives you a lot of flexibility in practice, you can stop a container with docker stop, start it again with docker start or restart it with docker restart.

What you cannot do though is, you cannot change a container. You cannot for example change the port mapping of an existing container. Containers are immutable. Once created, they retain the configuration they were created with. Makes sense if you don’t want to end up in a configuration spaghetti.

If you want to change the runtime parameters of a container, you’ll have to stop the container and remove it. Then you need to create a new container from the image with new runtime parameters. Let’s change our container so that it runs in the background.

Let’s issue the command docker stop my-nginx to stop the container.

Execute docker ps and note that the container has disappeared.

Run docker ps -a, this will list all containers, also the ones that are stopped. You’ll see your container here. If you used docker start my-nginx now, your container would start, but this is not what we want.

Run docker rm my-nginx. This will remove the container. I usually remove my unused containers immediately.

Let’s start a new container with new parameters:

docker run --name my-nginx -d -p 80:80 nginx:1.10.1-alpine

We added -d to start the container in detached mode, so it will run in the background. http://localhost should display the page we saw before.

Use docker logs my-nginx now to see the logs, or docker logs -f my-nginx to leave logs open in terminal and follow the requests.

Use docker inspect my-nginx to see the details of your container.

Executing commands in a running container

This an interesting possibility. Let’s do the following:

docker exec -ti my-nginx /bin/sh

This command starts an interactive shell in our running container. You’ll get a shell with root access and will see all the Linux file system.

If you look around you’ll see that the container bears all the characteristics of a full blown Linux OS. If you type env you can review the environment variables, you can also look at the file system, if you wish.

You can use docker exec to execute a command in a running container. I haven’t used this in any serious business scenario, yet. I just use this option to look inside containers.

Let’s use exit to leave the shell and return to our terminal.

Data in Docker containers

Now that we learnt so much about containers, let’s see another crucial aspect. Containers are meant to be stateless. This means that they are reproduced exactly as they were defined and they don’t carry any information with them from any runtime.

What do you need to do about this? If you change some data in a container during runtime, like data in a mariadb container for example, that data will be available only in that specific container instance. If you stop and restart your container your data will still be there. But if you stop and remove your container to start it with new parameters your data will be lost.

Code behaves in a similar way. You can copy your code when you build your image (I’ll show that later). When your code changes you have to re-build the image, destroy your containers and start new ones with the new image.

In order to manage data and code changes in a meaningful way, we can share volumes (meaning data volumes) between the host and the container. This is super important and I use this in all containers that I have.

Using volumes I can keep my mariadb data outside the container, or I can serve my local development directory with a Docker container.

We will use a config file on the host computer and mount it into our Nginx server.

Mount a config file

Let’s create a directory for this step, and create a file called nginx.conf inside. The absolute path of my nginx.conf file on my local machine is this /Users/marktakacs/Development/tutorials/docker/nginx.conf.

For the sake of the tutorial let’s copy the default nginx configuration from the container into the nginx.conf file on the host. This doesn’t make much functional sense, it’s just a technical example. Let’s use this content:

user nginx;

worker_processes 1;

error_log /var/log/nginx/error.log warn;

pid /var/run/nginx.pid;

events {

worker_connections 1024;

}

http {

include /etc/nginx/mime.types;

default_type application/octet-stream;

log_format main '$remote_addr - $remote_user [$time_local] "$request" '

'$status $body_bytes_sent "$http_referer" '

'"$http_user_agent" "$http_x_forwarded_for"';

access_log /var/log/nginx/access.log main;

sendfile on;

#tcp_nopush on;

keepalive_timeout 65;

#gzip on;

include /etc/nginx/conf.d/*.conf;

}

We’ll map this file as a volume into our container. As a result our nginx.conf file on the host machine will be shared with the container. If you change the file on the host, the container will pick up the changes.

Let’s docker stop my-nginx and docker rm my-nginx and then recreate the continer with the following command:

docker run --name my-nginx -d -p 80:80 -v /Users/marktakacs/Development/tutorials/docker/nginx.conf:/etc/nginx/nginx.conf:ro nginx:1.10.1-alpine

I added the part that that starts with -v, this maps the local directory to the container. Make sure that you use your own local path as the first parameter after -v. /etc/nginx/nginx.conf is the path of the nginx.conf file in the container, you can find this information on the image’s page on the Docker Hub, too.

:ro means that we mount the volume in read only mode.

Now our container uses the config file on the local machine. How can you test this?

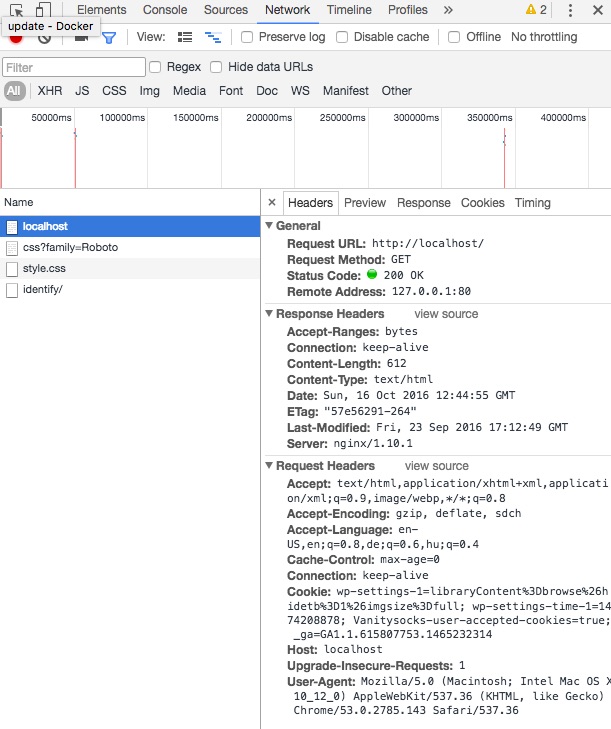

Open the nginx.conf file locally in a text editor like Vim, and remove the # from the line that says #gzip on;. You just uncommented the gzip feature of nginx, now nginx will send the responses compressed.

Restart the container so it will pick up the new configuration with docker restart my-nginx.

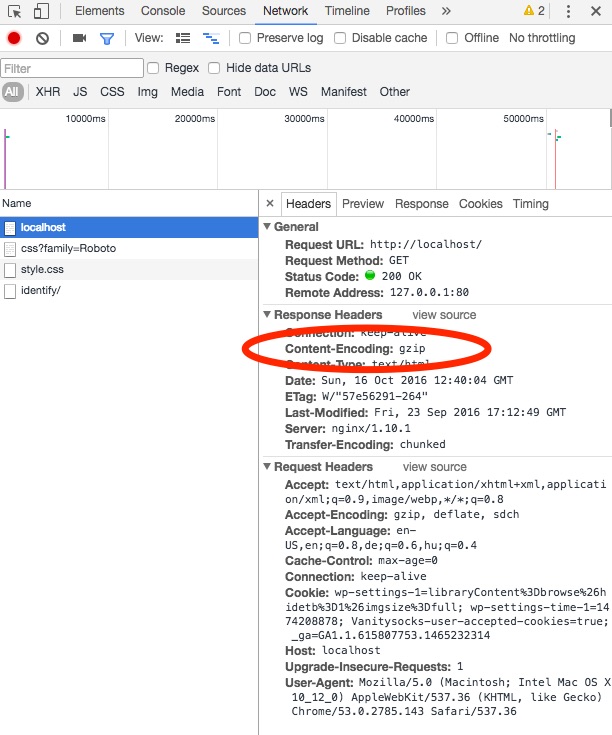

You can check compression in Chrome developer tools, under the Network tab and clicking the entry ‘localhost’. This is my response before and after the change.

We changed the configuration of our nginx container from the outside!

Using source code from the host

Wow, how about source code? Let’s add a webpage to nginx with another volume mapping. Create a directory called src and create a file called index.html in that directory. Copy this inside:

<p>Hello world</p>

docker stop my-nginx and docker rm my-nginx before we recreate it. Use a command similar to mine:

docker run --name my-nginx -d -p 80:80 -v /Users/marktakacs/Development/tutorials/docker/nginx.conf:/etc/nginx/nginx.conf:ro -v /Users/marktakacs/Development/tutorials/docker/src:/usr/share/nginx/html:ro nginx:1.10.1-alpine

We added a new volume -v parameter to the command. It points to the src folder on the host (please use your own full path) and mounts it to /usr/share/nginx/html in the container. Again I got the container path of html files on Docker Hub. If you go to http://localhost now, you should see a familiar hello world page.

Now the magic starts. Open your favorite text editor and change the message from Hello world to Hello docker or whatever you like.

You don’t need to restart you container now. Just refresh the page and smile, smile and smile some more. Welcome to a basic local development scenario with Docker.

If you want to start a project or pilot with some new tech, don’t think installation, brew or package management as your first choice. Just grab a docker images and start coding.

If you ever used python’s virtualenv or node’s nvm, you’ll immediately understand the significance of this moment.

The tools I’ve given you so far are good enough to run containers both locally and even in production. To get you started with more real-life use cases, I want you to meet two other possibilities.

How to build your own Docker image?

It’s very likely that you’ll need this feature when you build your proprietary environments. I use a custom Docker image for my node server, for example.

With the custom image I have the possibility to add my configuration files to the image and run installation for my node packages when the image is built. This way my node environment will become part of the image and I can start various containers with the same configuration.

In most use cases people add proprietary users in custom images, so that they don’t have to run their servers as root.

There are a lot of different scenarios and uses cases for building custom images. You’ll find a lot of help online for specific niches and problems.

In this post I’ll give you the basics to get you started.

In order to build your own image, all you have to do is add a file called Dockerfile to your project. The Dockerfile is just a text file, we use a text editor to add the build steps to the image.

Every build step in your Dockerfile will create a new layer in your image. This is very important.

Think of layers as snapshots on top of each other. If there is a change in a layer, the image will only rebuild starting from that layer and building every consecutive layer. The layers below the changed layer will remain intact. This is called layer caching.

I hope you’re starting to feel the potential time, effort and headache savings that layer caching brings to the table.

Let’s create your image now. Open your Dockerfile in a text editor. The file has the following format:

#Comment

INSTRUCTION arguments

We must, yes must, start the Dockerfile specifying which image we derive our image from. Use the FROM instruction to do this. Let’s use our good old nginx image to start from. Create a file called Dockerfile next to your nginx.conf on your local machine with the following content:

FROM nginx:1.10.1-alpine

MAINTAINER [email protected]

COPY ./nginx.conf /etc/nginx/nginx.conf

Our goal is to copy our nginx.conf from the local machine into a custom nginx image. This will give us an image that has gzip turned on by default. (Make sure you use the nginx.conf from the previous step where we uncommented the line that turns gzip on).

MAINTAINER is an instruction where you can specify yourself or your organization as the maintainer of the image. Put your email address there. COPY will copy the local file into the image.

Every line creates a new layer in our image. The process of creating an image from a Dockerfile is called building.

Build the image with docker build -t zip-nginx:1.0 ..

I used -t zip-nginx:1.0 to give a name and a version tag to my image. Note the . at the end of the line, it tells Docker to build an image from the Dockerfile in the current directory.

If you issue the command docker images in terminal now, you should see a new image called zip-nginx on the list.

Let’s start a container with the command we used to use, just remove the mounting of the config file, because we do not need it in this image, since we just made it part of the image itself. Don’t forget to change the image name to zip-nginx. I changed the container name, too. My command looks like this:

docker run --name my-zip-nginx -d -p 80:80 -v /Users/marktakacs/Development/tutorials/docker/src:/usr/share/nginx/html:ro zip-nginx:1.0

Looking at http://localhost in your browser will result in the Hello world example, and if you check the Network tab in the developer tools, you’ll see that the response comes gzipped by default.

We just created a new image that has a small functional improvement compared to the original one.

You can find the complete Dockerfile reference here.

Docker compose

We use docker-compose to define and run multi container applications. I use compose to start up my local development environment with the database, wordpress and node components. Compose has a very similar syntax to the docker command line tools, but with compose we use a file called docker-compose.yml by default.

This post is long enough already, so it’s better if I dedicate another post to this topic. While you wait you can read the official docker-compose documentation.

Wrap up

I really hope you successfully followed along all the steps here and got a grip on Docker. In my case, when I understood all of the above, I was able to go after issues on-line more effectively. I connected the dots and had a good idea where to look for a remedy for certain challenges.

I hope you feel more confident now and ready to move on with your projects. I wish you good luck and great success.

You can drop me a comment if you have a question or suggestion. Follow me on Facebook and Twitter, I’m working on more tutorials on Docker and some other stuff.

If you are still reading this, sorry for the long post, here is a potato :)).