- Why is Docker compared to virtual machines? What is the difference?

- How are containers isolated?

- Linux containers and Windows containers

- Next steps

This the second part of the Docker introduction article that I published recently on my blog and medium.

My goal is to give you a gentle introduction to Docker with practical examples, explaining what Docker is, what you can achieve with it, why you’d want to use it and what benefits you may expect.

I’d definitely suggest to start with the first post, because that’s where we cover the basics.

This introduction is a bit higher level, than a step-by-step, code-along tutorial. I decided to start the series on this level, so that less techie people may also find value in this introduction.

You can find code-along Docker tutorials for free on my blog and my youtube channel, if you prefer a more techie approach. I’ll keep adding more hard-core tech stuff, so stay tuned.

In this article we’ll cover the following points about Docker:

- Why is Docker compared to virtual machines? What is the difference?

- How are container resources isolated?

- Linux containers vs Windows containers

Why is Docker compared to virtual machines? What is the difference?

We defined Docker in the first article like this: Docker is a technology that you can use to bundle your application and its dependencies into one entity, called a Docker image.

With the use of Docker you can add your application code, your application’s configuration and the server program that runs your code to a Docker image. This means that a Docker image contains your application and its runtime environment, too.

The Docker image is your deployment entity.In the Docker world, you build a Docker image, and then you ship the image and run the image with standard Docker tools.

This means that you are shipping your application together with its environment in the Docker image.

You can use standard Docker commands, like docker run, to start up one or multiple Docker containers from your Docker image.

In my articles I often use the terms Docker image and Docker container somewhat interchangeably. The Docker image is the file system snapshot that defines the container, as we have seen in the previous article. The only difference is that a container is a running instance of the image. You can start multiple containers from one image. Please keep this distinction in mind as you read on.

Since the Docker image contains your application and its environment, the main use case of Docker is to standardize and simplify environment setup, configuration and provisioning.

There are various design best practices that you’ll use when you use Docker in your projects. My favorite design point of view is, that I think of a Docker image as one application service, meaning one main process running in a container.

So in my design planning workflow a front-end server will manifest as one Docker image, a backend API service will be another Docker image, a database will be another image, a message queue will be another image and so on… (We’ll return to databases later, because their placement in containers is a tricky point.)

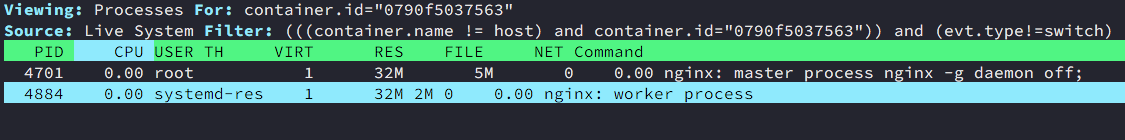

One container will feature one main process, not more. Some containers have multiple running processes on the technical level, like the Nginx image, but these processes all belong to the Nginx server, so they belong to one logical service. The image shows the master and worker processes running in an Nginx container.

So, I like to think of images and containers as application services and I think of Docker as a great tool to decompose my application stacks into layers, services and modules.

Let’s address the big question now: Why is Docker compared to virtual machines so often?

If you think of a virtual machine, it’s a complete operating system running on a server that runs a hypervisor. A VM runs an OS kernel, runs multiple system services, has additional programs, tools, files and configuration options.

On the contrary, a Docker image (or container) is geared towards a specific purpose and it does not feature additional processes besides its main purpose and it does not contain too much bloated stuff.

The comparison of Docker with VMs is so significant, because VMS are used to isolate application services just like we isolate application services with Docker containers.

Depending on your virtualization strategy, you may separate your application services running multiple services on one VM or running a single service instance per virtual machine.

The single service instance per VM pattern gives complete isolation. The main benefit of such a setup is that the isolated services have their dedicated CPU and memory resources and faulty behavior is isolated into the VM and won’t bring down your other service instances.

Both VM isolation patterns are resource intensive due to the overhead of the VM. Besides this, VM startup times bring latency to the changes you apply to your stack, like updates or scaling out your services.

Here is when Docker comes into play.

Docker containers are an operating system level virtualization technique.

Operating system level virtualization means, that the kernel of the operating system provides services that enable isolated user-space instances. These instances are called containers. You can read more about this on Wikipedia.

The idea of Linux containers is basically this: You take a Linux machine and build isolated virtual environments (i.e. containers) right on the Linux operating system level that have dedicated CPU, memory, block I/O, networking resources, plus you make sure that the processes, file systems, users and networking are isolated.

From the user perspective a container on your Linux machine will look like a separate Linux machine with its dedicated resources, programs and processes.

The above definition sounds very much like a virtual machine in the sense that both a container and a virtual machine has its dedicated resources and resource limitations, plus the resources and programs are isolated from other containers or virtual machines.

The big difference between Linux containers and virtual machines is that Linux containers run on top of the kernel of the host operating system. Linux containers share the Kernel of the host, and they provide isolation to the process(es) that run in the container.

In case of virtual machines, you use an entire virtual machine to isolate your processes.

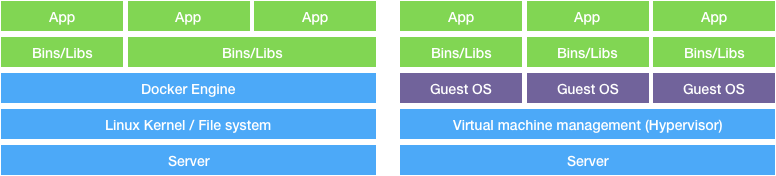

The below figure shows the isolation scenario with Docker containers (on the left) and virtual machines (on the right):

Docker started out as Linux based operating system level virtualization technology, but nowadays Windows based containers are also supported as we’ll see later in this post.

Docker is a very tempting solution for your applications, because containers are much more light-weight than virtual machines. The above figure clearly shows that you wont’ have the overhead of the Guest OS in each app service if you’re using Docker containers.

You can deploy multiple Docker containers on a single machine (physical or virtual), this gives you the opportunity to better utilize the resources of your servers.

Containers are smaller in size than virtual machines. Think hundreds of megabytes to a few gigabytes in case of VMs vs. a few megabytes to a few hundred megabytes in case of containers.

This makes containers faster to deploy and faster to start up and scale.

The startup time of a Linux cloud VM is usually in the minutes range, while a container starts up in a matter of seconds. (This varies depending on the use case. I put together a 2GB Docker image for data crunching that I’m not too keen to re-build or re-start all the time, so it’s always around on my Mac. I’ll show you in a later post how you can build your own.)

With the use of Docker you can run more workloads on a single host than you’d be able to run with virtual machines. This is often referred to as higher workload density.

This is a clear benefit, but before jumping into an all-in transformation program, it’s better to assess where Docker would best fit into your application landscape.

Isolating your services with containers has some drawbacks, too. Containers share the kernel of the host system, which means that containers are less isolated than virtual machines.

This raises security concerns. A container may take control of the entire host (under certain conditions, I’ll write about this, too), therefore it is essential to learn about security aspects of containers.

Faulty behavior may affect the kernel and thus have a negative effect on other containers, too.

Another important aspect of the container and VM comparison is to see the way these components work together.

In case of VMs you’ll set up your networking preferences, load balancers, firewall rules between your VM instances.

In case of Docker containers, you’ll typically deploy your containers on cloud hosts that are connected on the host level, but what you really need is interoperability on container level, not just host level.

Docker provides out of the box tools to set up and manage interoperability of containers with Docker networks, Docker volumes, Docker stacks, Docker services and Docker’s built in orchestration solution Swarm.

With these tools, you can accomplish various provisioning and configuration management tasks. All these tools are widely used in production.

Container adoption is increasing every day, for common cloud use cases containers are the simplest and most economic solution. It’s important to understand the differences between containers and vms, so that you can take the right design decisions in your projects.

How are containers isolated?

Docker containers running on a Linux host are isolated with the use of Linux kernel features.

Kernel namespaces isolate containers so that processes running in different containers cannot see or affect processes running in another container on the same host.

Containers also get their own network stack. This way you can start multiple containers listening on the same port.

You can, for example, start two Nginx servers in two containers both listening on port 80. This means that these containers listen on port 80 on their respective container network stacks, not on port 80 of the host machine.

The containers can access each other on the Docker network, and you can set up networking to access the containers from the outside.

Resource allocation and limiting is achieved with control groups. Cgroups are also a feature of the Linux kernel.

Linux containers and Windows containers

We’ve seen that Docker containers run on Linux machines and share the Linux kernel of the host system.

Docker started out as a container management platform for Linux machines. The containers shared the Linux kernel and the Docker images were all built with Linux tools and binaries.

As a result of a cooperation between Docker and Microsoft, today you can use containers on Windows server machines, too. These containers are called Windows based containers and they share the kernel of the Windows server machine and the Docker images are built with Windows tools and Windows binaries.

You’ll find both Linux based and Windows based containers on the Docker Hub these days. A simple example is the Python repository on the Docker Hub that has image variants for both Linux and Windows server.

Today Docker containers are run on Linux servers and Windows servers in production.

You can develop Docker on Mac computers, too, but there is no production version on the Mac. The reason for this is that Docker containers require a Linux or a Windows kernel and the Mac does not provide this natively.

You can develop Docker on the Mac, because Docker’s native Mac app runs a small Linux VM under the hood that gives you a Linux kernel and the native Docker app hides the implementation details from you.

Similarly, you can develop Linux containers on Windows machines, in this case the Docker Windows app will run a small Linux VM under the hood.

Next steps

We have learned that Docker containers are an operating system level virtualization technology and they provide high level of isolation for your application components while they remain light-weight.

Containers are much lighter than virtual machines, because VMs use a Guest OS to isolate application environments, while containers share the same host OS kernel and therefore isolated components don’t carry the overhead of a Guest OS.

In the next posts we’ll learn the basics of Docker containers and images and we’ll also deep dive into the internal workings of containers and images and see a few interesting examples that help you understand how these tools work.